On the second day, the author was ready for somewhat bigger human settlements – comparably at least, in relation to the first day of calm relaxation in the middle of nowhere.

A lot to set eye and mind on despite there being nothing else but water, clouds and plants alongside Elbe-Lübeck canal

But since even on a well-caffeinated day it is important to get to a not-too-hectic start, two more hours of staring in amazement at impressive formations of clounds, and their reflections in the waters of Elbe-Lübeck canal, was a good lead-in to more.

Berkenthin’s Maria-Magdalenen church is greeting proudly from afar

“More” being stepwise still, though, starting with the village of Berkenthin, ca. 2100 inhabitants. As small as this village is, as rich and long is its history, reflected prominently by Maria-Madalenen church built in the early 13th century, famous for its medieval paintings on the walls and ceiling.

Art and culture are alive in Berkenthin still: a rather new piece of artwork are the so-called “canal herrings” by local artist Tim Adam. It points back to the old salt trading route and its historic meaning and value (as detailed in the previous blog entry).

Well, salty fish may be nice artwork, but else it is not a really an appealing mid-morning option; therefore, riding into Lübeck, home of world-famous marzipan by Niederegger, was a welcome change. If you feel that the company’s logo reminds you of something, than you are right.

And you will know for sure what it reminds you of when you stand in front of its real-life counterpart, Lübeck’s so-called Holstentor (Holsten gate), the signet of Lübeck which has been built in late medieval times and been part of the city walls and stronghold.

And you will know for sure what it reminds you of when you stand in front of its real-life counterpart, Lübeck’s so-called Holstentor (Holsten gate), the signet of Lübeck which has been built in late medieval times and been part of the city walls and stronghold.

And when you stand in front of the most formidable building of this merchants’ city, it is easy to understand why it made it onto one of the D-Mark bills.

And when you stand in front of the most formidable building of this merchants’ city, it is easy to understand why it made it onto one of the D-Mark bills.

From marzipan-sweet Lübeck and its 50-DM bill Holstentor to the geographical demarcation line of rather bitter times in German history, it is only a 20min bike ride to Schlutup where you find a little museum of this village’s time during the decades the inner-German border ran right through it.

When growing up only 50 km or so West of this village in the 1970s, we have always been scared by the grown-ups that little children who do not watch out when swimming in the Baltic Sea or riding their bike too close to the border would be shot without warning.

When growing up only 50 km or so West of this village in the 1970s, we have always been scared by the grown-ups that little children who do not watch out when swimming in the Baltic Sea or riding their bike too close to the border would be shot without warning.

And shot a lot of people were, in fact, as we all know.

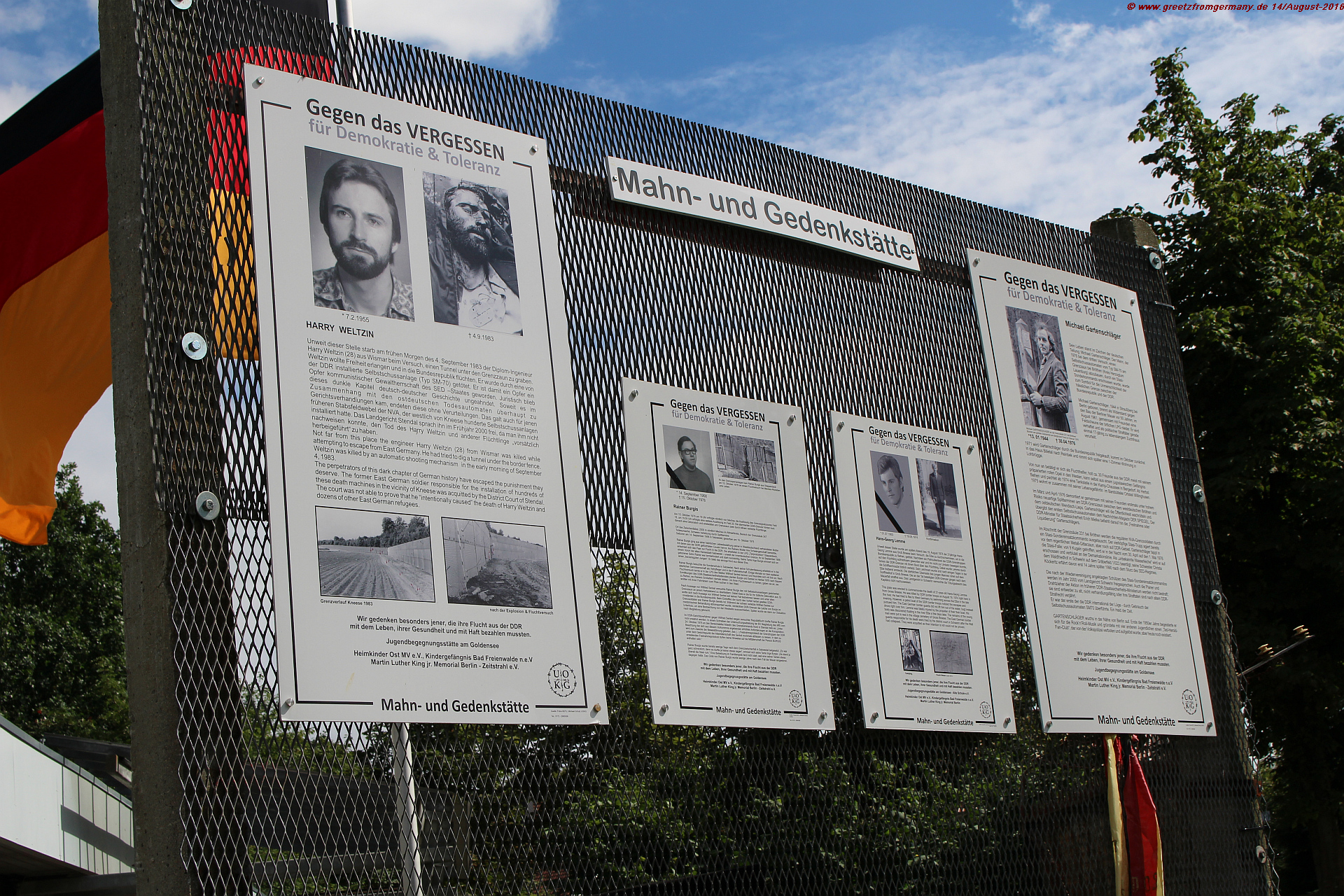

Cynically, even people from the West were shot – Andreas Gartenschläger, for one. He ended up on the Eastern side of the walls and barbed wires put up by Eastern Germany in 1961. Gartenschläger was 17 at that time – and sentenced to life-long prison after he and five of his friends protested the demarcation line, marked – gradually over time – by sentry guns, landmines and attack dogs installed between the two Germanies. Gartenschläger had to endure 10 years in prison, with long periods of detention in solitude, when Western Germany bought him out of prison. While his body was pretty broken by then, his mind apparently wasn’t as he organized the flight of another 31 Eastern Germans from his new home in Western Germany. As political activist, he took one of the sentry guns apart in 1976 and had this story published by the most influential political news magazines of those times, Der Spiegel. This activist initiative was repeated with another sentry gun a month later, in April 1976 – and on May 01, 1976 Gartenschläger was executed by more than 120 bullets fired off by Eastern German “security” who had the order to “arrest or destroy” Gartenschläger whenever he would set foot on Eastern German territory again.

In 2000, this execution was trialed – and the formerly Eastern German military men got away as “not guilty” – Gartenschläger carried a gun himself, so the court found it possible that the border control defended themselves. Three years later, the higher ranks were trialed as well – with one walking away as “not guilty” and the other one’s trial not being pursued any longer because of lapse of time. In 2006, Gartenschläger’s Eastern German former home town of Strausberg was asked to name a street after Michael Gartenschläger – and refused to do so on the political level.

These are the bitter thoughts adding to this otherwise sweet and salty blend of today’s impressions.

Lübeck’s city hall – a grand building still symbolizing the hightime of merchants‘ coalition „Hanse“ and the political benefits that were installed during these times as well – located not very far from where people, until as recently as 1989, were imprisoned, tortured and killed, if their political views were not sufficiently aligned with those of the government.